A ways back, in Lava Hot Springs, Idaho, I met a fellow named Dick who was warm and engaging – well, that’s an old story now. That’s pretty much how things go for us. Dick was trusting enough to share a bit of his journey, and I was happy to have met him. He mentioned a book, and I made a mental note. He mentioned it again a while later in response to a post of mine and I made a mental note again – but I didn’t bother to find it to read. My reading habits, and tastes, have changed on the road. I’ve found myself reading books to fit the path I find myself on. Digging deep in William Least Heat Moon’s PrairyErth while in the Tallgrass Prairie of Kansas was the right thing to do. Reading Steinbeck’s telling of the boys of La Paz helping his crew dig up marine samples in The Log of the Sea of Cortez gave shape to our time in Baja. Finding the space to read Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer just hadn’t happened. Till now. So, thanks, Dick, and sorry it took me a while.

In the settler mind, land was property, real estate, capital, or natural resources. But to our people, it was everything: identity, the connection to our ancestors, the home of our nonhuman kinfolk, our pharmacy, our library, the source of all that sustained us. Our lands were where our responsibility to the world was enacted, sacred ground. It belonged to itself; it was a gift, not a commodity, so it could never be bought or sold.

Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin wall kimmerer

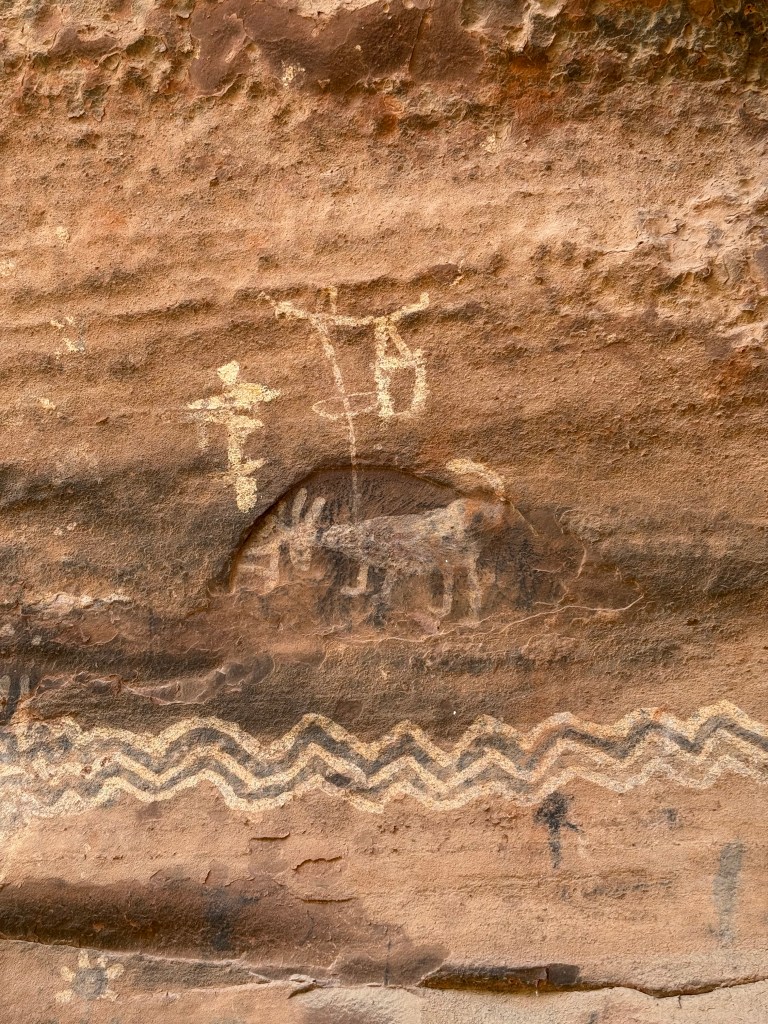

In our job with the US Forest Service, Holly and I live on land others have occupied – even if passing through – for about 15,000 years. Plants far longer. We have a bit of elevation here, and have lovely Pinyon Pines and Juniper. Small oaks and Manzanita make a scrubby understory. Nearby, on the riparian banks of the creeks, we have Cottonwood and Sycamore. We are proud that we have become trustworthy stewards of our little Red Rock canyon. We have come to understand the plants and animals here. We’ve met indigenous visitors – the people with true rights to this land – and learned what weights they carry. I’ve sat with little kids in a grotto of ancient art and talked about what is worth drawing. All that and more. The United States stole this land in 1875, and in a short 150 years has made quite a mess of it. We’ve poisoned the land and run off the critters, imprisoned or killed people who were simply doing their best to live in balance in the world, and claimed dominion over something we could have easily shared – all in search of a nonexistent Lake of Gold.

The Verde Valley where we live at the moment has a history of abundant plants and animals. Yucca and agave are plentiful. There are mule deer and javelinas all around – and mountain lions keeping them all in check. Bold ringtail coatis nose around. Even the Biblically discredited snake is welcome here. There is no embarrassment among the plants and animals, and the early people carefully found their place, listening to the plants and animals to learn how to be here without doing harm. It is their Covenant. Not a romantic idea, but it is inherently peaceful. In this valley, people came to understand the Three Sisters – how corn, beans and squash lived together and how they could provide enough, generation after generation, to allow the people to build small pueblos and develop deep-rooted communities. Kimmerer writes with love about the Three Sisters, and all the ways that plants teach us if we care to learn.

But then the Spanish came. In their blood was an emptiness which leads to yearning, and religion that drives people apart. Joy Harjo in An American Sunrise tells that the Eastern Indians of the Mvskoke banned Christianity:

”The old Mvskoke laws outlawed the Christian religion because it divided people. We who are relatives of Panther, Raccoon, Deer, and the other animals and winds were soon divided. But Mvskoke ways are to make relatives. We made a relative of Jesus, gave him a Mvskoke name.”

An american sunrise, joy harjo

The Spanish came with slave raids and priests. They came with their own sordid wealth and plans to steal more. Espejo came with money from marrying a 12-year-old from a wealthy family. He went north from Mexico looking for a Lake of Gold and was embarrassed to find people nearly naked, growing crops, and fishing along the Rio Grande and Verde rivers. Coronado came form the south as well, all the way into the land of the Kansa, also embarrassed at the poverty of people who farmed and fished and hunted and who did not destroy the land.

The complex pathologies of our modern life here, with Americans running off the indigenous and laying claims to the lands of waters of this part of the world, have become more clear. Kimmerer has clarified words for me, teaching that being indigenous to a place is a choice, a behavior, not a fixed state of being or not being. We are all migrants, and can all become indigenous if we learn to treat our particular place – even if one is nomadic – with respect and reciprocity. I feel that way about the West now. I’m finding its flow and long range views and its pathways. I don’t want to go back East with its relentless Colonial boot heel. But I suppose that is a myth I’m allowed only because I get to live in this astonishingly beautiful little canyon with its pueblo and its art.

And so I will follow the paths laid by other explorers, the ancient paths now paved and fast, looking in vain for something that has been underfoot all along.